While the focus of this article is to consider how to evaluate learning in a PBL experience, the practical application is much broader. Any classroom experience that involves dynamic or highly differentiated instruction fits the idea. In these and other situations, when teaching and learning aren’t uniform or rigidly structured, evaluation is difficult.

Hold in mind, then, the goal. To better evaluate learning in complex experiences, look to embed evaluation throughout the learning process.

In terms of PBL and other workshop-oriented approaches, students are often working on different concepts at different times, among other asynchronicity. As such, evaluating progress, learning, and skills tends to be a bit messy. Additionally, outcomes are rarely as straightforward as responding to questions on a test.

Even so, the question remains the same in any instructional approach: how can students demonstrate understanding and mastery?

How to evaluate learning vs. how to demonstrate mastery

This adjustment is mostly semantics, but making the change is important for one simple reason. The onus needs to shift. Students drive the perspective when it comes to how to demonstrate.

Therefore, the rest of the challenge becomes somewhat collaborative with students. How can you demonstrate mastery of this concept or skill? Show me what you know about this idea? Create a presentation or product on this topic.

In doing that, the teacher’s role becomes primarily one of accountability and support as well as clear definitions of mastery or growth. When thinking about evaluation in this way, the necessary features of the experience become a bit more clear.

Rubrics, Feedback, and Accountability

Foremost, begin with clarity on what mastery looks like in the desired areas of growth. Consider the content standards as well as cognitive and non-cognitive skills. With that vision in mind, compose a rubric that captures the entirety of that mastery without specifying the modality or medium. In this way, the rubric becomes generic enough to use to evaluate any student product or presentation.

With that rubric in mind, students are able to answer the question of how to demonstrate mastery by applying their ideas to the criteria. Additionally, students are able to reflect on progress in terms of current knowledge and current gaps or needs.

While students are working to determine how to demonstrate mastery, then, the teacher is able to likewise evaluate progress through simple conferencing protocols. These provide opportunities for giving feedback as well as holding students accountable for both their goals as well as the intended growth in knowledge and skills.

Example of the Process

To illustrate this point, consider the following scenario and examples.

In a project where students are designing a house floor plan for a customer, the students first decide how they want to present the final designs to the customer. They know from the rubric the content objectives that must be included, but they may choose from 3D models, prototype construction, posters and blueprints, and more.

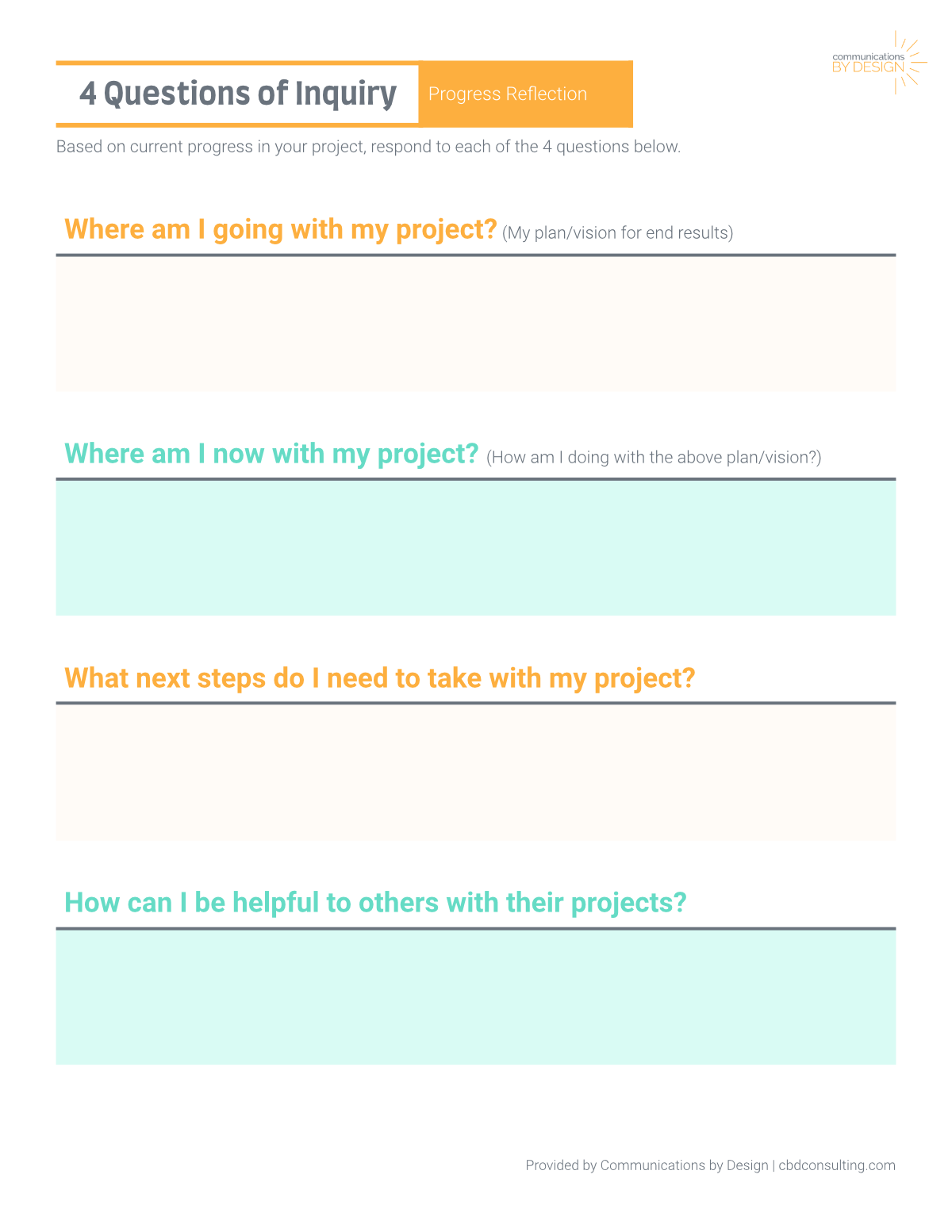

As they begin the process, the teacher implements a simple facilitation protocol like 4 Questions of Inquiry. During this protocol, students are periodically (weekly is about right for complex projects) asked to complete a kind of progress report by responding to the four questions on this graphic organizer (below–or make a copy in Google Docs here).

In conversations with the students and groups, then, the teacher is using these questions to follow up with the groups. The teacher asks about their current progress as well as next steps. The teacher also asks about how those students might be able to help other groups’ efforts. At times, the teacher offers suggestions to connect with another group to that end.

Students know that as the teacher checks in with groups, these questions will be the subject of conversation. The routine becomes predictable, and students know what to expect from the teacher as well as what the teacher expects from them.

Further and more importantly to this article’s topic, the teacher is able to evaluate at each checkpoint whether the progress observed and the students’ perception of that progress are in line with the necessary learning and pacing.

Finally, the end of the project contains no surprises for both the students and the teacher.

Evaluation as Part of the Process

The single summary statement of this contemplation is that evaluation ought to be part of the process. Rather than looking to evaluate learning in a single moment, embed evaluation into the experience and process. The results will be greater clarity on what students do and do not know or know how to do as well as ongoing opportunity to intervene when needed.